Time on the Corner: The History of Sheridan’s O.B. McClintock Clock

- Michael Dykhorst

- 4 hours ago

- 17 min read

****Author Note: The cover image comes from a painting discovered in Mary Christine “Christy” Love’s office in June 2025. The artist is currently unknown, and I would truly love to hear from anyone who might recognize it.

This article is dedicated to the memory of Christy Love. Christy was a generous supporter of the preservation of Sheridan’s history and the arts within our community. She held a deep appreciation for this clock and what it represented continuity, memory, and the quiet passing of time that connects generations of Sheridan residents to one another. In many ways, the spirit of preservation reflected in this story mirrors the care Christy herself showed toward our shared heritage.

Her enthusiasm, kindness, and belief that local history matters helped ensure that stories like this would continue to be told. ******

At the bustling corner of North Main and Brundage Street in Sheridan, Wyoming, one can find a relic of quiet grandeur, an elegant four-dial chime clock, perched high on the northeast facade of 109 North Main Street. Today, the building houses Best Out West Antiques, but the clock itself tells a longer, deeper story, one etched into the rhythms of the city’s past.

For over a century, this timepiece has stood sentinel over Sheridan’s historic downtown, its four luminous faces visible from nearly every angle of the intersection. Day after day, it has measured the hours with silent precision, even as the world around it has evolved. Installed during a period of civic pride and modernization, the clock once chimed the Westminster melody, its harmonious tones cascading over brick buildings, horse-drawn carriages, and, later, the steady hum of motorcars and city life. Though its music has long since faded into memory, its silhouette remains unmistakable: a piece of functional street furniture turned local icon.

More than just a clock, it is a witness. A silent observer of parades and protests, of new businesses opening and old ones closing, of lovers meeting beneath its shadow, and workers hurrying past to clock in at jobs long gone. Its presence anchors the corner with a kind of steady dignity, a reminder of a time when public clocks were as much civic monuments as they were mechanical marvels.

And while many passersby may no longer glance upward to check the hour, the clock endures—unchanged, unmoved, and unmistakably Sheridan. Its hands still trace the same circle they did in 1921, when the town embraced progress through precision. Though its chimes have been silenced, its legacy echoes through the very streets it was built to serve.

Sheridan: A City on the Rise

When Sheridan's iconic chime clock was installed in 1921, the city was in the midst of rapid transformation. Located at the foot of the Bighorn Mountains, Sheridan had emerged as a key hub for commerce, rail travel, agriculture, and coal mining. By the 1920s, it was enjoying the benefits of post World War I prosperity and embracing modern civic infrastructure.

Main Street, where the clock was ultimately placed, had become the beating heart of the town’s economy. Brick buildings lined the streets, many of which still stand today, at that time they housed hardware stores, dry goods merchants, cafes, and financial institutions like the Sheridan National Bank. Electric streetlamps illuminated newly paved sidewalks, and signs for local theaters and drugstores brought vibrancy to the street corners.

This was a time when towns and cities across America were investing in symbols of modernization. Public architecture began to feature electric clocks, streetlights, and ornate signage. Sheridan was no exception. Civic leaders sought to establish their city not only as a practical place to live and do business, but as a forward-thinking community aligned with broader national trends.

The installation of the McClintock chime clock in 1921 was emblematic of this movement. It was more than a bank fixture, it was a declaration. Located at the confluence of two busy streets, its presence projected reliability, order, and aspiration. For residents and visitors alike, the clock offered reassurance that Sheridan was keeping pace with the times, both literally and symbolically.

The decision to install a four-dial clock, rather than a simpler two-face version, also reflected ambition. Its glowing faces could be seen from every approach to the intersection, while the Westminster chimes echoed throughout the commercial core, marking time with elegance and confidence. In effect, the clock became a form of civic branding: a musical and architectural announcement that Sheridan was not just a frontier outpost, but a city with structure, beauty, and permanence.

The O.B. McClintock Clock Company

The O. B. McClintock Company of Minneapolis, Minnesota was the successor to the McClintock-Loomis Company which was at the heart of this revolution in public timekeeping quickly became one of the premier suppliers of commercial clocks in the United States. While smaller firms catered to local markets, McClintock built a reputation for producing large, electrified street, tower clocks, and products that blended mechanical precision with architectural grace.

Founded by O. B. McClintock, who previously helped launch the American Bank Protection Company (a pioneer in burglar alarm systems), the firm introduced the first and only business of its kind: a nationwide provider of electrical chime and clock systems. From its headquarters in Minneapolis, McClintock clocks made their way to every corner of the United States, resounding from Portland, Maine to San Diego, California, and everywhere in between.

By 1920, more than a thousand American cities had installed McClintock clocks, many of them mounted prominently on bank buildings. The company’s catalog boasted clocks with varying styles and what made them extraordinary was their combination of function and form; Roman or Arabic numerals, fluted or smooth columns. They could be mounted on poles, building corners, or freestanding pedestals. Their cases were constructed from cast iron or bronze, and their faces were often backlit with frosted opal glass while having a large illuminated clock face controlled by a master clock inside the building, linked to tubular chimes housed in elegantly crafted brass, bronze, and copper casings.

These clocks struck every fifteen minutes, faithfully echoing the revered Westminster chimes, from Big Ben at the Palace of Westminster in London, with the familiar refrain:

Lord, through this hour, Be Thou our guide; So, by Thy power, No foot shall slide.

These melodic tones, both practical and poetic, brought an air of dignity and reassurance to the communities they served. They were more than clocks; they were civic ornaments, marketing tools, and symbols of modernity and reliability.

In towns like Sheridan, where civic pride intersected with economic ambition, McClintock’s clocks became prestige items. The decision to install a four-dial Westminster chime model signaled that Sheridan wasn’t just keeping time, it was keeping up with national trends in design and technology.

George W. Perry and the Sheridan National Bank

The arrival of Sheridan’s four-dial street clock in 1921 was not a coincidence of trend or technology—it was a calculated decision made by one of the city’s most influential civic leaders: George W. Perry, then-president of the Sheridan National Bank.

A seasoned banker, former state senator, and businessman, Perry was instrumental in guiding Sheridan’s economic and civic identity into the 20th century. He believed strongly in progress and modern amenities, viewing them not only as conveniences but as reflections of a town’s values and ambitions. For Perry, a public chime clock was more than ornamental—it was a statement of permanence, refinement, and coordination.

At the time, the Sheridan National Bank stood prominently at the corner of Main and Brundage Streets. The intersection was among the busiest in the city, home to shops, drugstores, and many other businesses. Perry saw an opportunity to install something timeless, something memorable: a McClintock chime clock, visible from all directions and capable of sounding its presence with musical regularity.

In the Sheridan Post, dated August 6, 1921, Perry publicly announced the clock’s purchase. Perry had

commissioned the Westminster chime clock from O.B. McClintock, to be installed on the exterior corner of the bank. His decision was not only practical, it was aspirational. He envisioned Sheridan as a town of substance and sophistication, and the clock would serve as a symbol of both.

This clock is nine feet high with a thirty-inch dial, and will be established at a point about 20 feet high at the corner of Main and Brundage, being visible from four directions. It will have the cathedral chimes, striking the quarter hour in addition to the hour.

Perry understood that symbols mattered. Banks were not only financial centers—they were institutions of public confidence. By placing the clock in such a visible location, he tied the bank’s identity to order, consistency, and innovation. The clock didn't just tell time; it told a story—about Sheridan’s place in the modern world and about the men like Perry who helped shape it.

For years, the clock stood as an unofficial signature of the bank. It featured in advertising copy, directional instructions, and public events. Long after the chimes fell silent, the association between the clock and the institution that installed it remained unbroken.

Even beyond banking, George W. Perry was known as a progressive force in Sheridan’s political and economic life. As a state senator and member of various civic boards, he frequently championed modernization efforts. The clock was only one of many projects he supported that left a visible mark on the city.

By the end of that same month, on August 30, 1921, The Sheridan Post reported that the clock had arrived in town:

"CHIME CLOCK HAS ARRIVED" The handsome new Westminster chime clock... was received yesterday and will be installed probably next week... The timepiece has a very pleasing musical tone, strikes the hours, half hours, and quarter hours... It will be installed on the corner of the Sheridan National Bank and will be visible from every direction...

The article noted that the clock was eleven feet in length, with a 30-inch face, and that the total cost of purchase, shipping, and installation was approximately $2,000—a significant investment for the time, symbolizing the bank’s civic commitment.

By September 25, 1921, just weeks later, the clock’s installation was complete. The Sheridan Enterprise published a short notice celebrating its activation:

"BIG CHIMES CLOCK INSTALLED BY BANK" The huge chimes clock that is being placed on the corner of the Sheridan National Bank by that corporation is nearing completion… A professional clockman is here from the Minneapolis company from which the clock was purchased and is supervising installation...

Though Perry passed away less than a year later in 1922, his influence lingers in the legacy of that quiet monument on the corner. Every time a pedestrian looks up at the four illuminated faces, they engage, perhaps unknowingly, with a vision set into motion by Perry over a century ago.

Mechanics of Westminster Chime Clocks

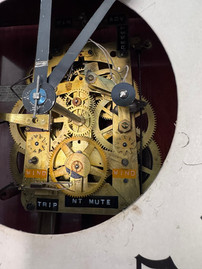

Above: Patent for Chime Clock showing the Mechanical schematic for chime mechanism showing camshaft, hammers, and chime rods. Patent no. 1,322,216 Patented November 18, 1919.

When Sheridan’s four-dial clock first rang out across Main Street in 1921, it did so using a sophisticated and carefully engineered mechanism—one that blended early electrical innovation with centuries-old musical tradition.

The Westminster chime melody, also known as the "Cambridge Quarters," originated in 1793 for the clock tower of Great St. Mary’s in Cambridge, England, and was later made famous by Big Ben in London. The melody consists of five chime rods or bells that produce a sequence of notes played every quarter hour. At the top of each hour, the full four-part melody is followed by a count of hourly strikes corresponding to the time (e.g., 3 strikes at 3:00).

McClintock’s Chiming System

The O.B. McClintock Clock Company used an electric motor-powered striker system for its chime clocks. This system typically involved the following components:

Timing Camshaft – A rotating shaft with fixed pins or cams that turned at a consistent rate (usually powered by an electric motor synced with the clock’s internal timekeeper).

Lift Levers – Small arms that were pushed upward by the cams at designated intervals (every 15 minutes).

Striking Hammers – Each lever controlled a hammer, which would fall onto a metal chime rod or bell when released, producing a distinct note.

Chime Rod Array – Tuned metal rods or bells, often mounted vertically in a wooden or metal soundbox behind the clock housing.

On a typical McClintock chime clock:

At 15 minutes past, one quarter of the melody would play.

At 30 minutes, half the melody.

At 45 minutes, three-quarters.

At the top of the hour, the full melody followed by hourly strikes.

Electric Innovation and Reliability

Unlike older mechanical tower clocks that required daily winding, McClintock’s clocks were designed for low-maintenance operation. Electricity powered both the hands and the chime striker. This was a significant advantage for bank buildings, where reliability and consistency were essential.

The strike control system was likely powered by a relay circuit that activated when the clock reached each quarter-hour mark. These pulses triggered the motor or solenoid mechanism that turned the camshaft, initiating the chime sequence. The entire process was both precise and elegant—allowing a single motor to control an auditory tradition that had once required a team of bells and a manual clockkeeper.

Below are photos of the Indoor mechanism that keeps the Clock in Sheridan running and on time. Photos taken by Michael Dykhorst in June 2025.

A Soundtrack for Downtown

Installed high on the corner of the building, the clock's chimes would have carried several blocks in any direction, especially in the quieter downtown soundscape of the 1920s. They offered more than the time: they added music to the rhythm of life. Whether striking out the noon hour or softly chiming a quarter past three, they marked both order and ambiance in downtown Sheridan.

Silence with Time

While the dials could be maintained relatively easily, the chime system was more complex. Over time, the hammers could fall out of alignment, the chime rods could crack or go out of tune, and motors could burn out. Though no official record remains, it is likely that Sheridan’s chimes were silenced sometime between the late 1930s and mid-1940s, possibly due to mechanical failure, cost concerns, or changing tastes.

Still, the framework likely remains inside the housing: silent, dusty, but once a marvel of public acoustical engineering.

Clock in Daily Life and Memory

From the day it was installed in 1921, Sheridan’s four-dial chime clock became more than a mechanical object. It became a part of the town’s emotional and practical landscape. The gentle rhythm of the Westminster chimes punctuated each quarter hour, calling shopkeepers to attention, letting schoolchildren know they were late, and reminding townsfolk when it was time to close up for the day. In an era before cell phones, digital displays, or even widespread wristwatches, this clock was the shared heartbeat of downtown.

Its location—anchoring the corner of Main and Brundage—ensured it was seen by nearly everyone. Locals gave directions by it. Businesses described themselves in relation to it. A 1922 advertisement for the Economy Drug Co. invited customers to find them simply by looking for the chime clock:

“Right across from the Big Chime Clock—YOUR Economy Drug Store.”

Newspaper ads and holiday messages referenced its music and presence. As early as 1924, the Sheridan National Bank had begun to build a symbolic identity around the clock’s chimes, publishing poetic ads like:

“They typify the ideal relationship between a man and his God as well as a man and his neighbor.”—The Sheridan Post-Enterprise, July 20, 1924.

By Christmas of the following year, the connection between clock, community, and conscience was crystalized with the now-familiar refrain:

“Lord through this hour / Be Thou our guide, / So by Thy power / No foot shall slide.”—The Sheridan Journal, December 24, 1925

These phrases, which are drawn from the traditional Westminster clock prayer, reflect how deeply the chime clock had become part of Sheridan’s cultural identity. It was no longer just an instrument of time it was a voice, a presence, and for some, a kind of musical reassurance.

A Familiar Companion

Even after the chimes fell silent, the memory of their sound endured. Generations later, longtime residents recall the bells, even if they were never personally heard. The idea of the clock striking every quarter hour still resonates with nostalgia. It lives on in local lore, in photographs, and in the architectural familiarity of the clock itself.

Sheridan’s chime clock has been described by residents as “the one constant on Main Street,” a quiet companion to a town that has otherwise seen constant change.

Present in Silence

Today, though its music no longer floats through the air, the clock still speaks—through its form, its legacy, and the way it continues to shape how people move through, and remember, downtown Sheridan.

It remains a meeting point, a photographic icon, and an ever-visible link to the city’s golden age. Though the bell’s echo has faded, the image of the chime clock—always present, always watching—continues to keep Sheridan on time in more ways than one.

Clocks Across America

Above: 5 of the same model clock manufactured by O.B. McClintock and Company shown around the USA. Left to Right: Hendersonville, North Carolina (Photo from Google), West Hollywood, California (Photo from James Harrod in 1995, Via Bill Emery), Roanoke, Virginia (Photo from Google), and San Antonio, Texas (Photo from Instagram), American Fork, Utah (Photo by Michael Dykhorst December 2025).

While Sheridan’s chime clock stands tall and proud at the corner of Main and Brundage, it is not alone in its heritage. Across the United States, a handful of similar four-dial clocks many built by the O.B. McClintock Clock Company or comparable firms can still be found guarding intersections, mounted to banks, or standing freestanding in city centers.

Each of these clocks tells not just time, but a story of civic pride, architectural preservation, and communal identity. Some of the ones that are just like Sheridan's are....

Hendersonville, North Carolina

Location: Main Street

Type: Four-dial freestanding clock

Status: Fully restored, operational

Notes: Hendersonville’s downtown clock was restored during a Main Street revitalization campaign in the 2000s. The city treated it not as a relic, but as a focal point of community identity. The dials were cleaned, the mechanisms refurbished, and the lights rewired. It now serves as both a photo-op and an audible marker of the town’s rhythm.

West Hollywood, California

Location: Santa Monica Boulevard

Type: Wall-mounted four-dial clock

Status: Intact, not operational

Notes: This rare wall-mounted clock remains fixed to the side of a historic commercial building. Though its chimes are silent, it retains its original McClintock casing and dials. Preservationists have discussed restoring the clock’s functionality as part of a broader heritage overlay district effort.

Roanoke, Virginia

Location: Market District

Type: Freestanding four-dial clock

Status: Maintained and semi-operational

Notes: Roanoke’s downtown clock has had a mixed history of maintenance. Though not a McClintock model, it reflects the same era and style. Restoration efforts in the 1990s preserved its frame and dials, though the chimes remain out of service.

Manitowoc, Wisconsin

Location: Former jewelry store

Type: Four-dial McClintock-style clock

Status: Restored

Notes: Located outside what was once a jeweler’s shop, this clock was privately restored in partnership with local historical societies. The chime mechanism was too damaged to repair, but the rest of the clock was brought back to working order.

San Antonio, Texas

Location: Municipal Plaza

Type: Pedestal-mounted clock

Status: Fully operational

Notes: Restored to its original glory, San Antonio’s clock includes a digital chime system installed to replicate the Westminster melody. Though its mechanism has been modernized, it maintains the aesthetics of early McClintock models.

Other Notable Examples:

New York City, New York: Several four-dial clocks in Manhattan still operate in historic commercial districts.

Winter Haven, Florida: A downtown street clock serves as a civic landmark with restored lighting and timekeeping.

Concord, NC: Restored during a civic beautification project.

Granger, TX: Freestanding and decorative, no longer operational.

Copake, NY: Situated in a historic park, used for educational programs.

Woodbury, NJ: Maintained by the city as part of its Main Street heritage.

Panama City, FL: Features an intact four-dial clock similar in scale to Sheridan’s.

O’Fallon, IL: Restored after public outcry when the city considered removing it.

American Fork, Utah: No information found

Each of these clocks reinforces an important point: while the mechanisms may differ, and their conditions may vary, the story is largely the same. These clocks were built not just to keep time, but to inspire it to punctuate daily life with grace, reliability, and local pride.

Sheridan’s clock belongs in this distinguished family not just preserved, but admired, both for its design and the story it continues to tell.

Preserving the Chimes

All across America, cities both large and small have faced the same question: What do we do with our silent clocks?

As the 20th century progressed, the chimes that once echoed through downtowns gradually fell silent. Motors wore out. Strikers broke. Replacement parts became rare. Some cities removed their clocks altogether, others let them quietly deteriorate. But in recent decades, a renewed interest in heritage preservation has sparked a movement, one that may offer a path forward for Sheridan’s beloved four-dial timepiece.

Learning from Other Cities

O’Fallon, Illinois, offers one of the most successful examples. When its historic street clock was slated for removal in the early 2000s, public outcry prompted the city to restore it instead. With the help of local fundraising and a professional restoration firm, the clock’s structure was stabilized, the dials were cleaned, and a modern digital chime system was installed that mimics the Westminster tones with high-quality speakers hidden within the case.

Winter Haven, Florida, took a similar approach, replacing the aged internal mechanism with a modern movement while retaining the original housing and restoring the lighting. Although the chimes were not reactivated, the restored dials and illuminated base have become a point of community pride.

In Manitowoc, Wisconsin, local historical societies partnered with private owners to bring a McClintock-style clock back to life—employing horologists who specialize in antique timepieces. Though the chimes could not be salvaged, the timekeeping function was fully restored.

Each restoration varies in scope and method, but all share a common outcome: the return of a functional and beautiful artifact to its community.

The Chimes

It no longer chimes. The melody that once floated over Main Street, rising with the sun and receding with the dusk, has faded into memory. But the clock remains mounted not only in iron and glass, but in the shared imagination of a town.

It is easy to overlook it now, standing silent among the blinking traffic lights and neon signs, dwarfed by the clutter of modern noise. But stop long enough, and you’ll notice what Sheridan has always had: a sense of place. A rhythm. A center.

Time doesn’t always announce itself in the same way. In 1921, it rang out in quarter-hour intervals, tuned to the key of Westminster and carried on mountain air. In 2025, it pulses through cell phones and digital screens. But one clock, mounted to a corner brick building, still carries the weight of every minute that has passed between then and now.

Its four dials remain a visual anchor. Its cast-iron housing bears the soft erosion of age. The lantern above still glows at night, but the voice that once marked the passage of time now stands silent.

And in that silence, it asks a simple question:

What would it take to hear it again?

Not just the chimes, but the confidence they inspired. The sense that a city could be measured, kept, and marked by the notes of something elegant. Something enduring.

What Would It Take in Sheridan?

Restoring Sheridan’s chimes would begin with a careful inspection of the interior. If any portion of the original striking mechanism remains—cams, hammers, rods it could be assessed for potential mechanical repair. If the internals are gone or unsalvageable, there are still viable options:

Option 1: Mechanical Restoration

Pros: Most historically accurate

Cons: Extremely rare parts, specialized labor, high cost ($50,000+ depending on condition)

Option 2: Digital Chime Retrofit

Pros: Affordable, invisible installation, programmable chimes

Cons: Less authentic, requires hidden speakers and controls

Estimated Cost: $12,000

Option 3: Hybrid

Preserve or restore the visible hardware (lantern, faces, hands) and combine it with a non-visible digital chime system, allowing for a public “restart” without compromising historical integrity.

Funding and Partnerships

Several potential sources could support such an initiative:

State or local historic preservation grants

Sheridan Downtown Association

Wyoming Cultural Trust Fund

Corporate or private sponsorship (e.g., banks, local foundations)

Public fundraising and awareness campaigns

A plaque or small interpretive sign could be added to the base of the clock, explaining its history, restoration, and legacy inviting residents and visitors alike to understand what they’re hearing, and why it matters.

Bringing the chimes back wouldn’t just restore a sound it would reconnect the city to an era, a memory, and a shared rhythm. It would turn heads again at the quarter-hour. It would make time musical in Sheridan once more.

The Clock That Remains

Above: Images of the Clock during the day and at night, demonstrating it continues to keep time and is illuminated at night. Photos by Johan Dykhorst.

Over the many years, the copper of the clock’s casing discolored and turned to a blue-green patina, which in this author's opinion should be left untouched if the clock ever undergoes restoration. It gives the clock authenticity.

Some may call it nostalgia. But for those who remember, or wish they could, the clock is a monument not to the past, but to time itself. Its melody may be lost, but its meaning has never gone quiet.

In every town, there is a corner like this. A fixed point. A pause in the march of time. In Sheridan, Wyoming, it happens to be a clock. One that deserves, perhaps, not only to be seen, but heard once more.

Photos from Various Sources.

Photos over time showing the Clock on Bundage and Main Street. - CLICK TO ENLARGE.