Echos of the Stage: A small history of the Opera Houses of Sheridan

- Michael Dykhorst

- Oct 19, 2025

- 20 min read

***PLEASE NOTE***

THIS IS NOT A COMPLETE LIST OF SHOWS OR PERFORMANCES HELD AT THE DIFFERENT OPERA HOUSES.

Opera Houses in small town america were symbols of culture and aspiration. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, opera houses were as much a fixture of Western towns as saloons and train stations, serving as cultural epicenters where communities gathered to experience the arts. These venues were more than just entertainment halls; they were symbols of a town’s ambition, sophistication, and desire to establish itself as a respectable place on the frontier.

Sheridan, Wyoming, was no exception, standing out with not one but four (known) grand opera houses that brought sophistication and entertainment to the heart of the frontier. The Kirby (formally Akins), Bishop’s, Oscar Nelson’s, and The Cady were prominent fixtures in Sheridan’s cultural and social landscape. Each of these venues served as a vital gathering place where residents experienced the arts, celebrated milestones, and built a sense of community.

In many towns, the term "opera house" was deliberately chosen to avoid the less respectable connotations associated with the word "theater." At the time, "theater" was often linked to bawdy entertainment, gambling, and other unsavory activities. By contrast, “opera house” evoked refinement and high culture, even in towns where actual opera performances were rare.

This naming convention helped establish these venues as symbols of cultural aspiration and community pride.

Opera houses like The ones in Sheridan were far more than venues for performances. While they hosted traveling productions, vaudeville acts, and even the occasional operatic performance, these spaces also functioned as vital centers of community life. They were places where townspeople gathered for dances, lectures, political rallies, and other civic events. The opera houses were hubs of activity.

The Kirby Opera House, for instance, was a popular venue for high school graduations and public speeches, while Bishop’s, Nelson’s, and The Cady hosted a mix of touring theatrical productions, musical acts, and community celebrations. These venues brought a touch of urban culture to a remote frontier town, fostering a sense of connection between Sheridan and the wider world.

The establishment of opera houses was often championed by women in the community who viewed these venues as a means to elevate the moral and cultural standards of their towns. In Sheridan, women’s groups such as local temperance organizations and civic clubs likely played a role in advocating for the construction and maintenance of venues like The Kirby, Bishop’s, and The Cady. These women saw the opera houses as spaces where families could gather for wholesome entertainment, free from the influence of saloons and other less reputable establishments. Their efforts helped ensure that Sheridan’s opera houses were not just places of entertainment but also centers of education and community engagement.

The Kirby, Bishop’s, Nelson’s, and The Cady Opera Houses each reflected the architectural trends of their time. While none of these venues rivaled the grand opera houses of urban centers, they were impressive structures for a frontier town like Sheridan.

With its prominent location, the Kirby Opera House (formally Akins) became a landmark of downtown Sheridan. Its design included a spacious auditorium and a stage that accommodated everything from theatrical productions, lectures and speakers, High School Commencement to musical performances. Bishop’s and The Cady were similarly designed to serve multiple purposes, with seating arrangements that could be reconfigured for dances, lectures, or other events. In contrast, Oscar Nelson’s had a stage but served mainly as a Saloon.

While these opera houses were relatively modest compared to their urban counterparts, they were a source of pride for Sheridan residents. Their construction signaled that the town was not merely a transient settlement but a place with cultural aspirations and a commitment to community life.

The establishment of opera houses in Sheridan mirrored a broader trend in small town America during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. These venues were seen as symbols of progress and permanence, marking a community’s transition from a rough-and-tumble frontier settlement to a more established and refined town.

The presence of not one but these four opera houses underscored the town’s ambition and cultural sophistication.

Today, only one of Sheridan’s opera houses remains partially standing, as the third story that the Opera House Occupied burnt in 1906. This surviving building serves as a silent witness to the cultural and social gatherings that once defined Sheridan’s community life. Meanwhile, The Kirby, Nelson’s, and Bishop’s opera houses exist only in records and photographs, their stories preserved through the efforts of historians and local residents.

These venues were once central to Sheridan’s identity, hosting performances, dances, and public events that brought people together. Their loss is a poignant reminder of the shifting cultural and economic landscapes that have transformed small towns across America.

The decline of Opera Houses, despite their cultural significance, began in the early 20th century. The advent of cinema and radio brought new forms of entertainment that were cheaper and more accessible than live performances. Movie theaters quickly became the dominant cultural venues in towns like Sheridan, while opera houses struggled to compete.

At the same time, advances in transportation made it easier for people to travel to larger cities for entertainment, further diminishing the role of local opera houses. By the 1930s, many venues had either closed or been repurposed.

In Sheridan, as in many other towns, the decline of the opera houses marked the end of an era. While they had once been symbols of cultural aspiration and community pride, they eventually became relics of a bygone time.

According to a 1945 article in The Sheridan Press, Thurston Aiken, though the building was often called the Akins Opera House, built the venue around 1892 as a roller skating rink, when skating was wildly popular nationwide. The earliest known newspaper reference to it appeared on April 2, 1892.

Not Much of the early history of the Akins is known, but from the 1945 article we know it was built by Thurston ‘Thurst’ Aiken. So who was Thurston Aiken? On Ancestry I was able to find a family tree from Thurst’s Great-Grandson Robert Aiken, and from that, I was able to craft a biography specifically for this book. Thurston William “Thurst” Aiken was born on February 18, 1856, in Atchison County, Missouri, to Thomas Avery Aikens and Margaret Skerritt Ross. By the age of four, he was living with his family in Boulder Creek, Nebraska Territory, which would later become Boulder, Colorado.

At 22, Thurston experienced significant life changes. His father passed away in Valmont, Colorado, on April 16, 1878, and that same year, he graduated from the University of Colorado Preparatory School, Class of 1878. His mother, Margaret, died a few years later, on July 10, 1881, in Valmont, Colorado.

On March 16, 1882, Thurston married Harriet Mae Niver in Boulder, Colorado. The couple welcomed their first child, Claude William Aikens, on April 11, 1884. According to the 1885 Colorado state census, Thurston, then 28, was listed as the head of the household, living with Harriet, 21, and their one-year-old son, Claude. His occupation was recorded as a merchant.

Around 1886, Harriet’s father, Robert Grant Niver, moved to Sheridan County, Wyoming, and it’s believed that Thurston and his family relocated there around the same time. On August 11, 1888, the Aikens welcomed their second child, Florence Pearl Aikens, who was born in Sheridan, Wyoming. Just a month later, on September 11, 1888, Thurston was appointed the first postmaster of Pass, Wyoming, a small settlement north of present-day Parkman.

According to notes taken by Wyoming historian Charles G. Coutant before 1899, Thurston “entered into the stock business,” aligning with family stories of ranching and cattle work. On August 20, 1891, Thurston and Harriet had their third child, Bernard Robert Aiken, born in Sheridan. By 1892, newspaper records mention “Akins Opera House,” a notable establishment in the community.

The Sheridan Enterprise reported on June 1, 1893, that Thurston had completed a frame saloon and restaurant, which he operated successfully. Two years later, in April 1895, the Aikens welcomed another daughter, Verna Marie Aikens.

In September 1899, the family moved from the Pass Creek area to Sheridan so Thurston could manage his opera house more effectively. By 1900, the Aikens were living on Wyoming Avenue in Sheridan. In 2007, Helen Graham of the Wyoming Room at the Sheridan Fulmer Public Library identified their 1907 address as 326 Wyoming Avenue.

Thurston wore many hats during his time in Sheridan. In 1901, he served as the town’s marshal, but by 1907, he was working as a traveling salesman. Thurst also owned a candy store called Akins Candy Store. That same year, the family suffered the loss of a baby, who is buried in Sheridan.

Thurston eventually left Sheridan, although the exact date is unclear. By the 1910 census, he was living in Juneau, Alaska. He passed away on May 16, 1910, in Douglas, Alaska, from heart disease and was buried in Evergreen Cemetery in Juneau.

From 1892 until 1904 the opera house was known as the Akins Opera House. As far as records show it was the first Opera house in Sheridan. It is also unclear why it was spelled Akins when Thurston’s last name was spelled Aiken.

The building eventually was remodeled and in April 1903 the grand opening was heralded by the local newspaper on April 16, 1903, with headline reading, “The First Benedict; Benevolent and protective order of the Elks will occur at Akins’ Opera House” it went on to say “New Akins Opera House will receive its formal Opening”.

Sheridan entered a new age of cultural refinement as the Akins Opera House opens its grand doors. The inaugural event featured a full orchestra, dramatic performances, and a Grand Ball after the performance. The Akins also boasted new scenery, new stage setting and new lighting system, all electric lights with dimmers, etc., so as to give the audience and performers every advantage of a new up-to-date theatre.

This marked a pivotal moment in the town’s history, transforming Sheridan into a hub of artistic expression and social gatherings.

The Akins Opera House hosted performances that ranged from traveling theatrical troupes to local talent showcases. The transformation marked Sheridan’s shift from a frontier town to a more established and culturally ambitious community. Newspaper records from the time reveal the lively events that took place at the Akins Opera House.

An April 8, 1904, issue of the Sheridan Post records that the Akins Opera House hosted a performance organized by the Ladies Circle of the Congregational Church. However, the same issue reports that the venue had been renamed the Kirby Opera House, leased by Sumption & Kay, who had ambitious plans for its future.

“They declare they will run it as a first class playhouse,” the article states. “A new heating plant and ventilation system will be installed, the stage settings will be enlarged and improved, and a competent manager will oversee operations at all times. The building will also be expanded to provide spacious quarters for Company ‘D’ of the Wyoming National Guard. The public will be glad to learn that this opera house has been acquired by men who make a success of everything they undertake.”

The Kirby Opera House was named after J. Ira Kirby, a prominent local figure and businessman (sometimes referred to as Ira J. Kirby). His obituary, published decades later, highlights his contributions to the community. So who was John Ira Kirby? John Ira Kirby was born on August 11, 1869, in Woodford County, Illinois. In 1876, his family moved to Young County, Texas.

By August 1889, Kirby and his brother George B. Kirby had ventured north, arriving in the Sheridan area with a small herd of cattle that would become the foundation of the Kirby family’s extensive ranching operations.

The brothers initially settled near Rosebud Creek in Montana, where they established a ranch and a post office named “Kirby” in their honor. By the spring of 1890, John Kirby had joined the O4 Bar Ranch, a large cattle operation owned by Hardin and Campbell. Within a year, Kirby was promoted to oversee the entire ranch’s operations, a position he held until the ranch dissolved around 1899 or 1900.

Following the ranch's closure, Kirby moved to Sheridan, where he entered the world of business. Partnering with John Webber, he became a co-owner of Kittleson Hardware, a well known local establishment. The store operated under the name Kirby & Webber until Webber sold his interest to John Ladd, after which it became Kirby & Ladd. Eventually, the hardware store was sold to J.B. Jouvenat and renamed Jouvenat Hardware.

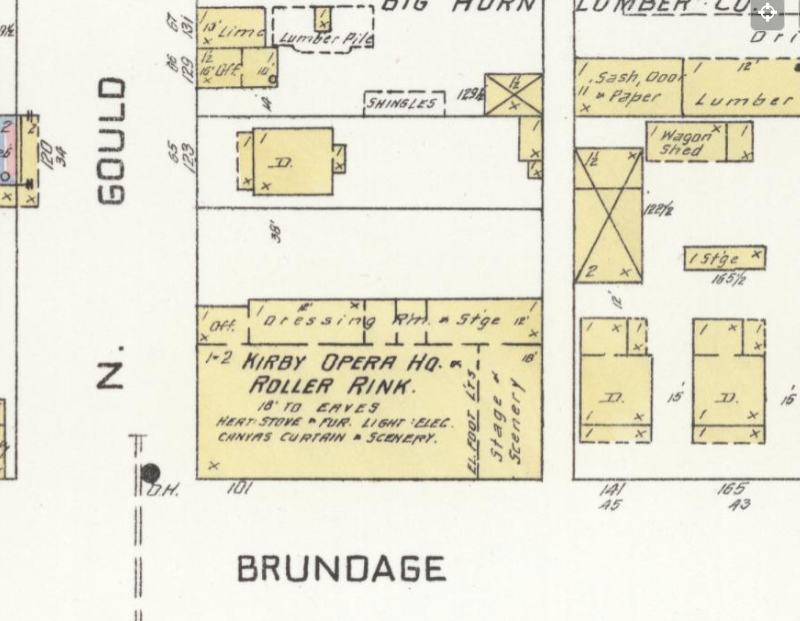

As far as it is known, in 1903, Kirby purchased and revitalized the opera house, located at the corner of Brundage and Gould Streets. Under his ownership, the Kirby Opera House became a focal point of Sheridan’s cultural and social life. The venue hosted plays, concerts, community events

and even served as the headquarters for Company ‘D’ of the Wyoming National Guard. Guardsmen used the hall for drills and other activities.

The opera house was not just a community gathering place—it was a source of pride for the city, attracting performers and audiences from across the region. Kirby’s military connections also enhanced the venue’s prestige; as a lieutenant colonel in the Wyoming National Guard, he frequently worked to ensure the militia had access to modern, well maintained facilities.

Sadly, the opera house’s prominence faded over time. By 1916, it had ceased operations as a theater. The building was later repurposed as a garage for Scales Motor Company before being demolished. Today, the site serves as a parking lot, but its legacy as a cornerstone of Sheridan’s early entertainment scene endures.

In 1921, Ira Kirby relocated to Buffalo, Wyoming, where he took on the role of receiver of public monies at the U.S. Land Office.

While the Kirby Opera House no longer stands, its memory, and that of its namesake, continues to echo through the stories of Sheridan’s vibrant past.

Photos of the construction to finish of the Scales Motor Inc building that stood on the corner of Gould and Brundage Streets in Sheridan. This building was torn down in recent years. Photo's from Downtown Sheridan Association.

Before there was the grand Akins or the well remembered Kirby Opera House, Sheridan had a more modest venue that left behind more questions than answers, Bishop’s Opera House.

Built in the early 1890s, this short-lived opera house was the brainchild of Joseph C. Bishop, a London-born businessman who had settled in Sheridan after years of moving across the American frontier. Bishop was known around town for his Pioneer Business Agency and for being deeply involved in civic life. By 1894, he was listed in the Sheridan City Directory as a theatrical agent, living at the Windsor Hotel, and actively promoting shows and events held at his namesake venue.

Though details about the interior and programming of the opera house are scarce, local newspapers like The Sheridan Post regularly featured ads and announcements for performances there between 1892 and 1895. It seems to have been a central part of Sheridan’s early efforts to bring entertainment and culture to the growing town.

Tragically, Bishop’s life came to an abrupt end on October 22, 1895, when he died of heart disease reportedly on the steps of the building he had helped make a cornerstone of Sheridan’s cultural life. He was buried in Mount Hope Cemetery in an unassuming grave, just three feet from the southeast corner of Block L.

His story might have faded into obscurity if not for a strange twist: in 1998, a Xeroxed copy of the 1894 Sheridan City Directory turned up in the Wyoming State Archives in Cheyenne. No one knows where it came from or what happened to the original, but inside was Bishop’s name one last trace of a man whose dreams once brought music and applause to the dusty streets of Sheridan.

Though the building is long gone, Bishop’s Opera House is another reminder of the town’s early appetite for art and performance and of one man’s determination to build something meaningful, even if it didn’t last.

Oscar Nelson Saloon and Opera. While it might sound like an odd pairing to modern ears, back in the day, it was perfectly natural to sip whiskey while taking in a traveling vaudeville act or a local musical performance. And Oscar Nelson leaned into that blend of grit and glamour with gusto.

Located at the always busy corner of Main and Alger, the Oscar Nelson Saloon was a fixture in Sheridan from at least 1911 to 1916, its presence confirmed by a series of now highly collectible merchant trade tokens. These little tokens used at the time like reusable drink chips or promotional credits boldly stamped the business name as: Oscar Nelson Opera. It wasn’t just a bar it was a brand, one that declared itself both a haven for spirits and a home for the arts

Mentions in The Sheridan Post and The Sheridan Post-Enterprise suggest that Nelson’s joint offered more than just a stiff drink. Though no formal playbills or programs survive, the very use of the word “opera” in the name strongly implies performances were part of the draw—whether traveling vaudeville troupes, frontier musicians, or even impromptu local acts. It was, in many ways, the people’s opera house: loud, lively, and always within arm’s reach of the bar.

Unlike the more polished or purpose-built venues in Sheridan’s theatrical scene, the Oscar Nelson Saloon and Opera was unapologetically Western. No velvet curtains or carved balconies here—just sawdust floors, smoky lanterns, and a rough-and-ready crowd that might shout just as much at the barkeep as at the man on stage. But that was the charm. It was entertainment as raw and real as the frontier itself.

By the mid-1910s, Oscar Nelson disappears from city records, and with him went the hybrid saloon-opera model. Yet, the building itself never stopped serving the town. In fact, it still does.

Today, the same structure houses the Rainbow Bar, a local institution in its own right, serving drinks, stories, and memories under the same roof where Nelson’s patrons once raised a glass to the beat of the banjo or the punchline of a dusty traveling comic. The music may be louder now, the performers replaced by jukeboxes and neon, but the spirit of the place, blending camaraderie and performance, is remarkably intact.

So next time you find yourself inside the Rainbow, take a moment to imagine the scene over a century ago. The crowd may have worn spurs instead of sneakers, and the lighting came from oil lamps instead of glowing beer signs but one thing hasn’t changed: Sheridan’s never been shy about mixing its whiskey with a little showbiz.

Just about everyone in Sheridan knows the Cady, or at least the building that still carries its name. Perched on the northeast corner of Main and Alger, the Cady Building has long stood as a silent witness to the city’s transformation from a frontier outpost into a thriving regional center. But in 1895, this three-story structure was more than just bricks and mortar. It was a symbol of progress, refinement, and the aspirations of a growing town. (MOST PLACES REPORT IT BEING BUILT IN 1893...BUT IT WAS BUILT IN 1895.)

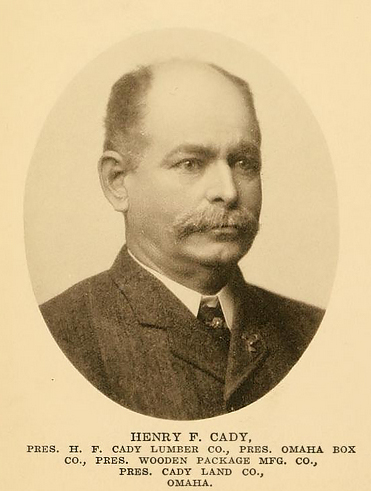

And behind that vision stood a financier and entrepreneur not from Wyoming, but from Omaha, Nebraska: Henry F. Cady.

Henry F. Cady was a prominent businessman and real estate investor in Omaha during the late 19th century. Known for his ventures in property development and his involvement in civic affairs, Cady had an eye for opportunity and a belief in the cultural power of architecture. His investment in Sheridan specifically the construction of the Cady Building represented more than a business deal. It was a vote of confidence in a young, energetic town poised for growth.

Though he never resided in Sheridan, Cady’s financial backing and name gave the building both prestige and permanence. To this day, few residents realize that one of Sheridan’s most important early structures was built with out-of-state capital an early example of the city attracting outside attention for its promise and potential.

When the Cady Building was completed in 1895, it instantly became one of Sheridan’s architectural standouts. Built of local stone and accented with ornamental ironwork, the structure rose three stories high and occupied a commanding corner in the city’s commercial district.

The first floor housed retail shops and local businesses, a mercantile, a barbershop and the office for the Sheridan Land Company. The second floor offered office space for professionals: lawyers, dentists, and doctors who gave the building a steady flow of foot traffic.

But it was the third floor that set the Cady apart.

Atop this enterprising edifice was the Cady Opera House, a performance space that would become the cultural heartbeat of Sheridan for the next decade. Modest by metropolitan standards but ambitious for a town of its size, the opera house featured wooden bench seating, gaslight chandeliers, a raised stage, and room enough for several hundred audience members. Entry was likely gained through an internal staircase or, during shows, possibly via a more dramatic external stairwell.

Though it bore the name "opera house," the venue hosted far more than opera. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, opera houses in rural America were flexible spaces that welcomed an eclectic mix of performances and events.

The Cady was no exception. Within its walls, audiences enjoyed:

Traveling Shakespearean troupes

Comedic farces and light-hearted cowboy skits

Magic shows and illusionists

Vocal and instrumental concerts

Lectures, debates, and public forums

Vaudeville performances—always a crowd favorite

Local schools used the stage for graduation ceremonies and music recitals. Political candidates delivered campaign speeches beneath its proscenium arch. Occasionally, fraternal organizations or church groups would rent the space for gatherings and community events.

For Sheridan residents many of whom worked long hours as ranchers, railroad laborers, or shopkeepers the opera house provided a rare chance to step into a world of imagination, art, and sophistication. It offered a space to dress up, socialize, and connect outside the routines of daily life.

The Cady Opera House drew a crowd as diverse as the region itself. Cowboys sat beside bankers; schoolteachers mingled with miners. Children attended matinee puppet shows, while courting couples opted for romantic plays at night.

For the town’s upper crust, the opera house offered the ultimate in public display box seats, evening gowns, and whispered gossip during intermission. But even those without social standing could feel like a part of something grand just by buying a ticket and taking a seat under the gaslit glow.

Tragedy struck in 1906.

That year, the Cady Opera House hosted what would be its final performance: a comedic play titled The Runaway Match. Reviews and programs from that night are scarce, but what is known is this after the curtain fell and the audience went home, something sparked in the dark. Sometime in the early morning hours, a fire broke out on the building’s third floor. The cause was never definitively determined: perhaps a backstage ember, faulty gaslight, or neglected electrical wiring. Whatever the source, the result was devastating.

By the time the flames were discovered, the fire had already gained too much ground. The third floor—and with it, the entire opera house—was engulfed. The rest of the building suffered significant water and smoke damage. Sheridan’s first true cultural venue was reduced to rubble and ash in a single night.

In 1907, the building reopened as the Helvey Hotel, repurposed for boarding and lodging.

In the 1980's another fire broke out in the building and this time people lost their lives. Many businesses have been in the building over time including several restaurants.

Many people remember the Cady House Restaurant and McEwan's Cafe or Sanford's Grub and Pub.

Below are some photos of Sanford's.

Today, the legacy of the Cady Building continues with Le Rêve Restaurant & Raw Bar, an upscale dining establishment that has garnered national recognition. Situated within the historic walls of the Cady Building, Le Rêve, French for, The Dream, offers a sophisticated menu inspired by French culinary traditions with creative global twists.

Founded by Christer and Gina Johansson, Le Rêve has quickly become a centerpiece of Sheridan’s revitalized downtown. Its velvet-accented interior, exposed brick, curated art, and live piano music subtly honor the building’s theatrical roots. The restaurant was recently named a James Beard Award semifinalist for Best New Restaurant in the country—an extraordinary honor that puts both Le Rêve and Sheridan on the national culinary map.

As diners sip wine and savor scallops or duck confit beneath the original brick arches, few may realize that above them once stood a stage where Sheridan’s earliest performers brought drama and joy to the frontier town. Yet in its way, Le Rêve continues the tradition—offering not just food, but an experience, an ambiance, and a sense of occasion.

In doing so, Le Rêve keeps the spirit of the Cady alive. A place of elegance, community, and artistry, once again.

Photos of Le Rêve taken October 19, 2025 by Johan Dykhorst.

The third floor the cultural crown jewel of the structure was never rebuilt. Perhaps it was the cost. Perhaps the town’s entertainment priorities had shifted. Or perhaps it was simply too painful to resurrect a space that had once pulsed with so much energy and community pride.

The loss of the Cady Opera House symbolized more than the destruction of a building. It marked the end of an era a time when live performance was central to community life and when a single stage could bring an entire town together.

Gone were the velvet curtains, the candlelit glow, and the rush of applause. In their place came projection screens, movie reels, and a more commercialized kind of entertainment.

And yet, the Cady’s spirit survives.

In oral histories, newspaper columns, and family lore, echoes of the Cady Opera House remain. Some longtime Sheridan families recall stories of grandparents who performed there. A few old photographs grainy, labeled in cursive hint at what once stood tall at Main and Alger.

The Cady Opera House may have only lasted thirteen years, but its cultural footprint was immense. It proved that Sheridan could dream bigger that a frontier town could support the arts, foster local talent, and welcome the world through its doors.

That it was made possible by Henry F. Cady a businessman from Omaha adds another layer to its story. It reminds us that visionaries come in many forms, and that sometimes, the soul of a place can be sparked by someone from far away who simply believes in its potential.

Today, as community theaters thrive and new venues continue to enrich Sheridan’s arts scene, we owe a quiet nod to the Cady. To the building. To the opera house. To the man whose name it bears.

And to the idea that every great town deserves a stage.

So if you find yourself standing at the corner of Main and Alger, pause for a moment. Look up. Imagine a packed third-floor hall glowing with lamplight, the air warm with anticipation, a hush falling over the crowd as the curtain rises. You’re not just looking at a corner in downtown Sheridan you’re looking at the birthplace of the town’s performing arts.

The applause may have faded long ago, but the echoes? They’re still there.

Photos of the Cady Building through the years. - Photos from Various Sources

Other Opera houses in the county

Dayton Opera House

Dayton’s opera house served as a beloved venue for plays, music, and civic gatherings. Likely housed in the top floor of the Croghan Hall/ Dayton Mercantile, it was a place where traveling troupes might perform one night, and schoolchildren take the stage the next. Locals recall its use for wartime rallies, dances, and community programs. For Dayton residents, it was a reliable place to connect, laugh, and applaud the talents of their neighbors.

Acme Opera House

Acme also had a venue known locally as an opera house. Located near the old Hotel in Acme. Still, for a time, this upstairs stage was a cherished fixture in the lives of Ranchester families, offering music and drama in the heart of town.

Information from:

Robert Aiken

The Wyoming Room at Sheridan County Fulmer Public Library.

The Wyoming Newspaper Project

Memories of "our hometown" Sheridan on Facebook

New York Optometry Association

Downtown Sheridan Association

WorthPoint

You truly catch the spirit of the early days of Sheridan and surrounding communities. I enjoy reading your articles. You make one feel like she is there in person watching all the activities. Great job. Can’t wait to read the next historical article. Bravo!

A very nice and informative historical article Michael Dykhorst! Great job! And your efforts are muchly appreciated, as I'm sure it took many hours of research and composition! An article you should be proud of! Thank you, Lynn Huson Kirkpatrick